My fellow Aussie and all-round good mate Pete Strutton is a marine biologist of a very different flavour to me. Whereas I work on bigger critters like whale sharks and (formerly) coral reefs, lobsters and fish parasites, Pete studies big-time plankton and nutrient cycle stuff in the open ocean. He also edited a book about marine ecology, which you can get on Amazon (even in Kindle format!). Pete’s at the University of Tasmania these days but formerly of Oregon State, Stony Brook University’s School of Marine Science and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. I caught up with Pete recently and asked him some questions about his work.

My fellow Aussie and all-round good mate Pete Strutton is a marine biologist of a very different flavour to me. Whereas I work on bigger critters like whale sharks and (formerly) coral reefs, lobsters and fish parasites, Pete studies big-time plankton and nutrient cycle stuff in the open ocean. He also edited a book about marine ecology, which you can get on Amazon (even in Kindle format!). Pete’s at the University of Tasmania these days but formerly of Oregon State, Stony Brook University’s School of Marine Science and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. I caught up with Pete recently and asked him some questions about his work.

AD: Hey Pete, can you tell us a bit about your favourite areas of research?

PS: In general my work concerns the intersection of biological and physical oceanography. In other words, I’m basically a biologist who knows enough physics to be dangerous. What this means in practice is that I try to investigate what causes variability in the productivity of the surface ocean. To do that I need to understand physical processes such as mixing and upwelling, that vary a lot in the ocean and deliver nutrients to the surface where they are consumed by phytoplankton for photosynthesis. This is important because the oceans are responsible for about half the photosynthesis that happens globally. Or as I’ve heard many times recently, every second breath we take is thanks to phytoplankton.

So like I said, most of the work I do is trying to understand how physics impacts biology, but recently I’ve become excited about the reciprocal process: Biological influences on physics. One cool example of this that I don’t work on is the contribution of ocean animals to mixing [of ocean water]. John Dabiri at CalTech was recently awarded a MacArthur Fellowship for his work in this area. What I have done some work on is how phytoplankton influence ocean warming. As we all know, phytoplankton absorb solar radiation to carry out photosynthesis. They actually re-radiate a lot of this energy back into the water as heat and fluorescence. So when the concentration of phytoplankton in the surface ocean increases, this means that there’s greater potential for trapping heat near the surface, rather than it penetrating more deeply into the ocean’s interior.

I’ve looked at two scenarios for the variability of phytoplankton (as measured by chlorophyll concentration) and the impact this has on ocean warming. The first is natural variability, and the case I looked at was the 1997-98 El Nino event in the tropical Pacific [Journal of Climate, 2004 17: 1097-1109]. More recently I’ve become very interested in the impact that geo-engineering scale blooms might have on upper ocean warming, particularly because the goal of these blooms is to ‘cool the planet’, but I think you’re going to ask me about that next.

AD: I want to ask you about ocean fertilization. I gather the basic idea is that plankton production (or algae growth) in the oceans is limited by one or more nutrients that are in short supply, so if you add that nutrient back in, you can encourage huge increases in productivity. This growth in plankton sucks carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and it becomes “fixed” (turned into animal tissue) and enters the food chain or, ultimately, sinks to the bottom of the ocean where it remains trapped for extremely long periods. This idea has been termed “carbon sequestration” and proposed as a way to offset or even reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide and thus ameliorate global warming. Where did this idea come from and who were the key players in its genesis?

PS: You’ve described the idea very well. The most famous and relevant example is that of iron limitation. For several decades, biological oceanographers wondered why chlorophyll concentrations (phytoplankton populations) were not higher in vast areas of the ocean, in particular the North Pacific, equatorial Pacific and Southern Ocean. When they did cruises to these areas, there seemed to be plenty of nitrogen, phosphorous and silicon available. These elements are all important building blocks for phytoplankton (by the way, carbon is never a limiting nutrient in the ocean). What was stopping phytoplankton from taking up these nutrients?

An important breakthrough came in the 80s by way of technological and analytical developments. John Martin’s group at Moss Landing Marine Labs in California developed careful techniques to accurately measure trace metal in the ocean. Iron, for example, is present in seawater at extremely low concentrations – it would take about 500 olympic swimming pools of seawater to make one 5 gram nail. Most of the sampling equipment we use in oceanography, including the ships themselves, are made of iron, so contamination was difficult to avoid. To cut a long story short, the Moss Landing group developed techniques to measure iron at parts per trillion concentrations. When they made uncontaminated measurements, it became clear that dissolved iron in the ocean was extremely low, particularly in the places I mentioned above. Phytoplankton were using up all the iron (in enzymes for photosynthesis among other things) before they ran out of nitrogen and the other nutrients. That’s why these other nutrients were sitting around unused.

There was a vigorous debate in the community as to whether low light, or consumption by higher trophic levels could be limiting nutrient uptake, but in the end, for the most part, the iron idea won out. John Martin further suggested that long term (tens of thousands of years) variability in dust inputs to the ocean could be regulating Earth’s climate (glacial cycles). He is (in)famous for saying ‘give me half a tanker of iron and I’ll give you an ice age’. He tells the story of this quote in a newsletter in 1990: ‘I first said this more or less facetiously at a Journal Club lecture at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in July 1988. I estimated that, with 300,000 tons of Fe, the Southern Ocean phytoplankton could bloom and remove two billion tons of carbon dioxide. Putting on my best Dr. Strangelove accent, I suggested that with half a ship load of Fe … I could give you an ice age. After which we all had a beer on the lawn outside the Redfield Laboratory’ (see picture [at top] of me having a beer on the lawn outside the Redfield lab 21 years later). I often use this quote in my lectures, although I sometimes get blank stares at the mention of Dr Strangelove.

Pete and colleagues loading iron into dispersal tanks during the SOFeX cruiseIn the 1990s, somewhat cautiously, oceanographers started testing this idea at sea, first in the equatorial Pacific (1993 and 1995), then in the other regions of interest: North Pacific and Southern Ocean.

Pete and colleagues loading iron into dispersal tanks during the SOFeX cruiseIn the 1990s, somewhat cautiously, oceanographers started testing this idea at sea, first in the equatorial Pacific (1993 and 1995), then in the other regions of interest: North Pacific and Southern Ocean.

AD: Can you tell us a bit about the SOFeX experiment and the SOFeX cruise in 2002?

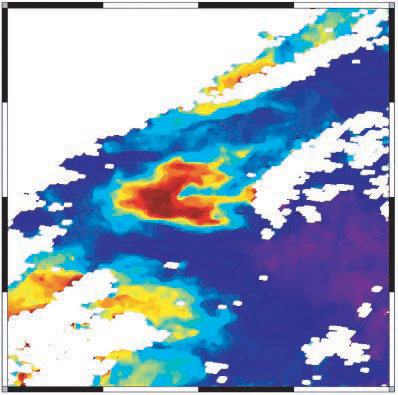

PS: So yes, in 2002 I was part of a US cruise to the Southern Ocean to perform a relatively large scale iron fertilization experiment. We left out of New Zealand and headed southeast towards the Ross Sea. We fertilized two patches about 15km x 15km. The two study areas were more than 1000km apart – our goal was to test the response of the phytoplankton in two parts of the ocean with different combinations of dissolved nitrogen and silicon.

AD: So now, eight years later, where is this “carbon sequestration” idea headed? Isn’t it just delaying the inevitable? Is it a viable option, or still controversial?

The “fish”: a device used to distribute the iron at a constant 10m depth. It was covered in rust, depsite being made of plastic!In general, in all of the experiments conducted so far, and there have been more than a dozen of them, blooms have been generated but the amount of ‘fixed’ carbon that ends up raining out of the upper ocean, let alone getting stored in sediments, is considerably less than hypothesized by Martin. There are theories as to why this might be, one of them is that the patches we’ve made to date have been too small, leading to dilution

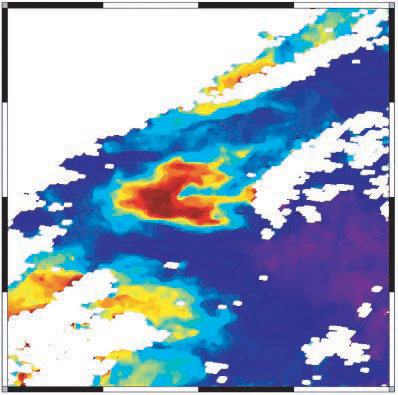

The “fish”: a device used to distribute the iron at a constant 10m depth. It was covered in rust, depsite being made of plastic!In general, in all of the experiments conducted so far, and there have been more than a dozen of them, blooms have been generated but the amount of ‘fixed’ carbon that ends up raining out of the upper ocean, let alone getting stored in sediments, is considerably less than hypothesized by Martin. There are theories as to why this might be, one of them is that the patches we’ve made to date have been too small, leading to dilution One of the plankton blooms produced during the SOFeX cruise, as seen from MODIS satellite. The red patch indicates higher productivity at their boundaries. Some are advocating that we perform even larger experiments, say 100km x 100km. My feeling, and I’m sure I’m not alone, is that iron fertilization is not the silver bullet that will save us from CO2-induced climate change. Nonetheless it is still talked about as potentially part of the solution, and it is also being considered by some in the context of carbon trading. That is, ‘I’ll go fertilize a part of the ocean with iron and suck up 10 tonnes of CO2, then sell that credit to you, Mr Coal-fired Power Plant Owner’.

One of the plankton blooms produced during the SOFeX cruise, as seen from MODIS satellite. The red patch indicates higher productivity at their boundaries. Some are advocating that we perform even larger experiments, say 100km x 100km. My feeling, and I’m sure I’m not alone, is that iron fertilization is not the silver bullet that will save us from CO2-induced climate change. Nonetheless it is still talked about as potentially part of the solution, and it is also being considered by some in the context of carbon trading. That is, ‘I’ll go fertilize a part of the ocean with iron and suck up 10 tonnes of CO2, then sell that credit to you, Mr Coal-fired Power Plant Owner’.

AD: SOFeX and some of your other cruises are definitely Science Writ Large. What’s it like to work on a UNOLS vessel and how do you balance the research interests of individual PI’s against the collective goals of the cruise? Is it fun or just a grind?

R/V Revelle, one of the two UNOLS vessels involved in the SOFeX experimenPS: Good question, particularly with regard to SOFeX. That cruise was very challenging. Even though we had two large ships in the end, there was still strong competition for space on the ship and this translated into competition for time to do science. We wanted to do lots of different tasks, like scan the region as quickly as possible to map the evolution of the patch as seen in surface properties, compared with detailed station measurements that required us to stay in one location for up to 6 hours. These types of sampling were often in competition with each other which makes it particularly challenging for the chief scientist (who constantly has people lobbying for time). To further complicate matters, I was running a drifter that was supposed to mark the center of the [fertilised] patch as it was moved around by the currents. We had real-time radio communication with this drifter, but on a couple of occasions, the GPS dropped out. So although we were getting updates from it, we had no idea where it was. We ended up spending way too much valuable sampling time searching for lost drifters.

R/V Revelle, one of the two UNOLS vessels involved in the SOFeX experimenPS: Good question, particularly with regard to SOFeX. That cruise was very challenging. Even though we had two large ships in the end, there was still strong competition for space on the ship and this translated into competition for time to do science. We wanted to do lots of different tasks, like scan the region as quickly as possible to map the evolution of the patch as seen in surface properties, compared with detailed station measurements that required us to stay in one location for up to 6 hours. These types of sampling were often in competition with each other which makes it particularly challenging for the chief scientist (who constantly has people lobbying for time). To further complicate matters, I was running a drifter that was supposed to mark the center of the [fertilised] patch as it was moved around by the currents. We had real-time radio communication with this drifter, but on a couple of occasions, the GPS dropped out. So although we were getting updates from it, we had no idea where it was. We ended up spending way too much valuable sampling time searching for lost drifters.

On a totally non-scientific note, the other challenge of SOFeX was the food. There was a breakdown in communication re the ordering of supplies prior to sailing and we ran out of a bunch of staples: Bread, eggs, milk, cheese. You’d reckon they could increase our beer allowance (1 per day) to compensate, but no. Oh well, we still managed to have the occasional ‘safety meeting’ in an undisclosed location…

[AD: If you have questions about geo-engineering or other parts of Pete’s research, post them in the comments and I’ll see if we can get some answer for you]

Tuesday, October 26, 2010 at 11:42AM

Tuesday, October 26, 2010 at 11:42AM